Stem cell aging is the root cause of human aging.

来源:Mesenchymal stem cells

2020-08-17

Aging is a common phenomenon in nature, characterized by the accumulation of genetic damage throughout the life cycle—and by imbalances between DNA damage and repair, leading to genetic mutations. During this aging process, every cell and organ in the body experiences some degree of functional decline or deterioration.

For example, as we age, our skin loses its elasticity, wounds heal more slowly than they did in childhood, and fractures take much longer to mend. In short, the diminished regenerative capacity of damaged tissues or organs is the most prominent hallmark of aging.

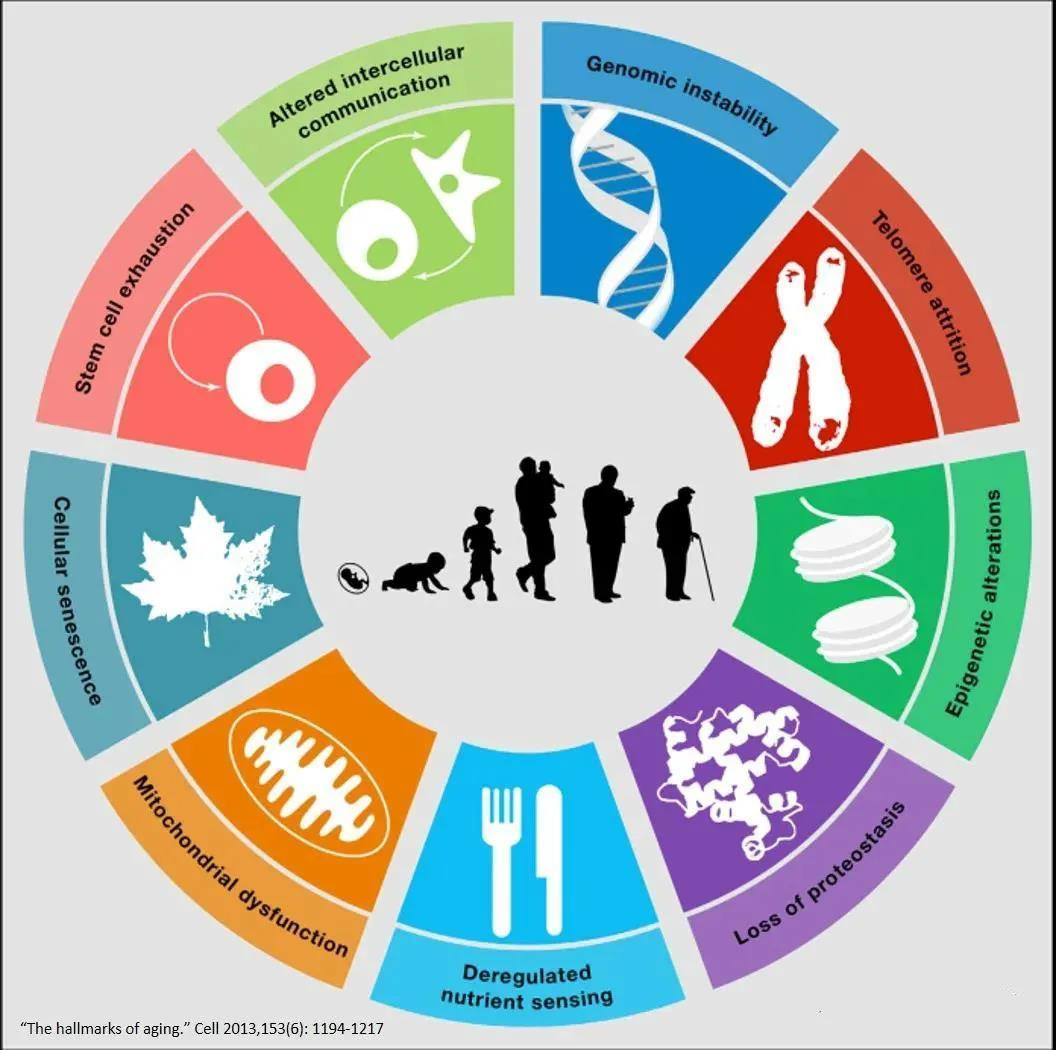

Characteristics of Human Aging

Nine hallmarks emerge during the aging process of the human body: genomic instability, telomere shortening, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, diminished nutrient absorption capacity, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication.

Aging is the cellular response to both intrinsic and extrinsic stresses, limiting the repair and renewal of damaged and aging cells. Harmful stimuli such as DNA damage, telomere shortening, oncogenic insults, metabolic stress, chromatin remodeling, epigenetic alterations, and mitochondrial dysfunction can all trigger this process. Importantly, aging is a dynamic, progressive, multi-step phenomenon that ultimately becomes irreversible.

Stem cell aging is influenced by several factors: telomere shortening, downregulation of the INK4a/ARF gene locus and cell cycle regulators, accumulation of DNA damage, epigenetic changes, alterations in mitochondrial structure, signaling pathways, and systemic factors.

In many human tissues, the decline in cellular division capacity with age appears to be linked to the gradual shortening of telomeres as cells divide. Telomere dysfunction impairs stem cell function by activating intrinsic cellular checkpoints and triggering alterations in both the micro- and macro-environment surrounding stem cells. Maintaining telomeres is one of the critical factors ensuring genomic integrity; when telomeres become dysfunctional or defective, it can lead to impaired proliferation and tissue regeneration, ultimately accelerating the aging process.

Histone acetylation controls chromatin structure, thereby influencing the regulation of gene expression. Enzymes with histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity also play a role in the aging process, most notably SIRT1 and SIRT2, whose expression has been shown to be age-dependent. Notably, SIRT1's function in MSC growth and differentiation declines as organisms age.

The accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations is closely linked to aging. As aging progresses, the buildup of mtDNA mutations leads to impaired respiratory chain function. Notably, several signaling pathways—such as the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT pathway—as well as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1), a key regulator of mitochondrial energy metabolism—are involved in this process.

Adult stem cells, found in various tissues throughout the human body, provide organs with the ability to grow and regenerate, ensuring homeostasis is maintained throughout life. The regenerative capacity of human tissues depends on the ability and potential of adult stem cells to replace damaged tissues or cells; therefore, the aging of stem cells can influence the overall aging process of the organism. All signs of aging—such as tissue degeneration—can be attributed to aging at the level of the body’s stem cells.

Aging of hematopoietic stem cells

Russian scientist Alexander A. Maximow introduced the concept of stem cells at a hematology conference in Berlin in 1908, and formally published an article outlining the essence of stem cells in 1909. However, modern stem cell research truly began in 1963, when Lou Siminovitch's team developed a method to detect hematopoietic stem cells and subsequently identified these cells—known as HSCs—in mouse bone marrow.

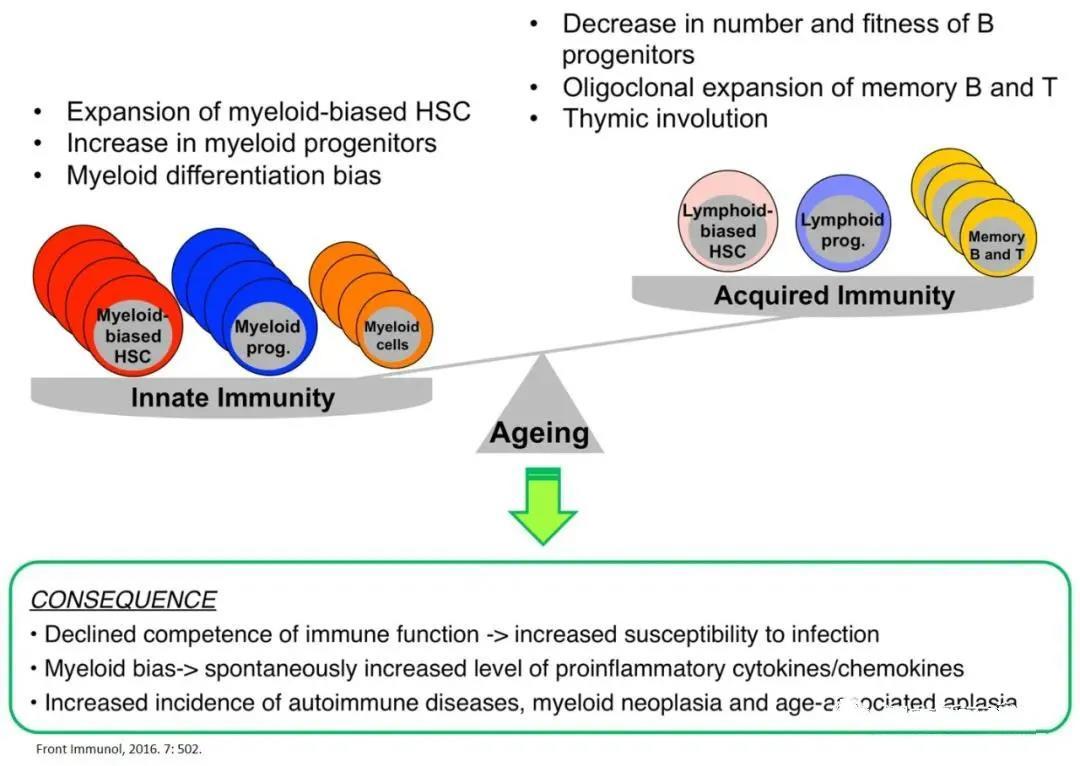

Immune Senescence

Hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow differentiate to produce immune cells that make up the entire immune system. When the adaptive immune system loses its ability to generate protective immunity, accompanied by a decline in the system's fidelity and efficiency, this condition is referred to as Immune Senescence A key feature of immunosenescence is the imbalance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory networks, characterized by persistent low-grade inflammation and an increased susceptibility to autoimmune responses.

The aging of the immune system stems fundamentally from the aging of HSCs.

Aging of the hematopoietic system manifests as Deterioration of the functions of the adaptive immune system and the innate immune system , the aging of these immune cells leads to heightened susceptibility to pathogenic microorganisms, reduced vaccine efficacy, and an increased risk of developing autoimmune diseases and hematological malignancies. Experiments involving HSC transplantation into T-cell and B-cell co-deficient mice demonstrated that age-related changes in the immune system's phenotype and function are primarily driven by functional alterations in HSCs during the aging process—and occur largely independently of thymic function.

Aging cells produce pro-inflammatory mediators and proteases, collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). SASP factors recruit immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, natural killer cells, and T cells, and promote inflammation.

SASP-induced immune cell recruitment is a fundamental physiological process that eliminates unwanted cells and drives tissue remodeling essential for development and homeostasis. However, if these pro-inflammatory signals and inflammatory processes are not properly regulated, they can fuel pathological inflammation—for instance, senescent smooth muscle cells may exacerbate vascular inflammation, while the cellular senescence of endothelial and smooth muscle cells could also contribute to the persistence of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Moreover, macrophages play a critical role in clearing senescent cells. Age-related changes in the local microenvironment, meanwhile, can alter macrophage function within tissues, leading to age-associated declines in both phagocytic capacity and antigen-presenting ability.

Aging of hematopoietic stem cells

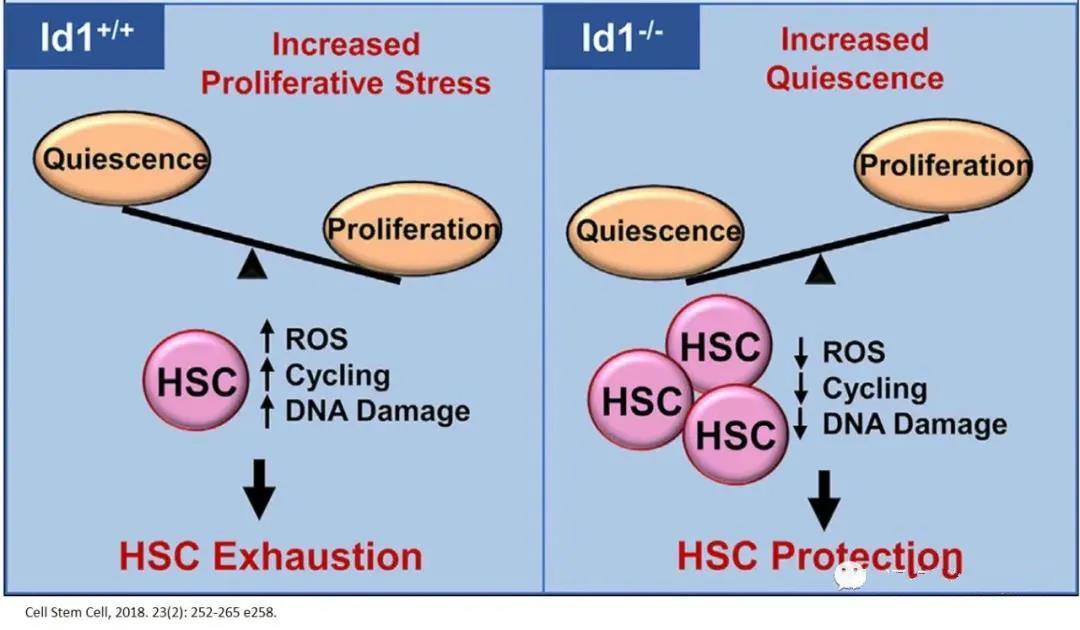

Most hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) remain quiescent under dynamic equilibrium, rarely undergoing self-renewal through the cell cycle or differentiating into progeny cells. The process of hematopoiesis is tightly regulated by both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, which together balance quiescence, self-renewal, and differentiation to ensure the stable maintenance of normal multi-lineage cells and facilitate systemic tissue regeneration.

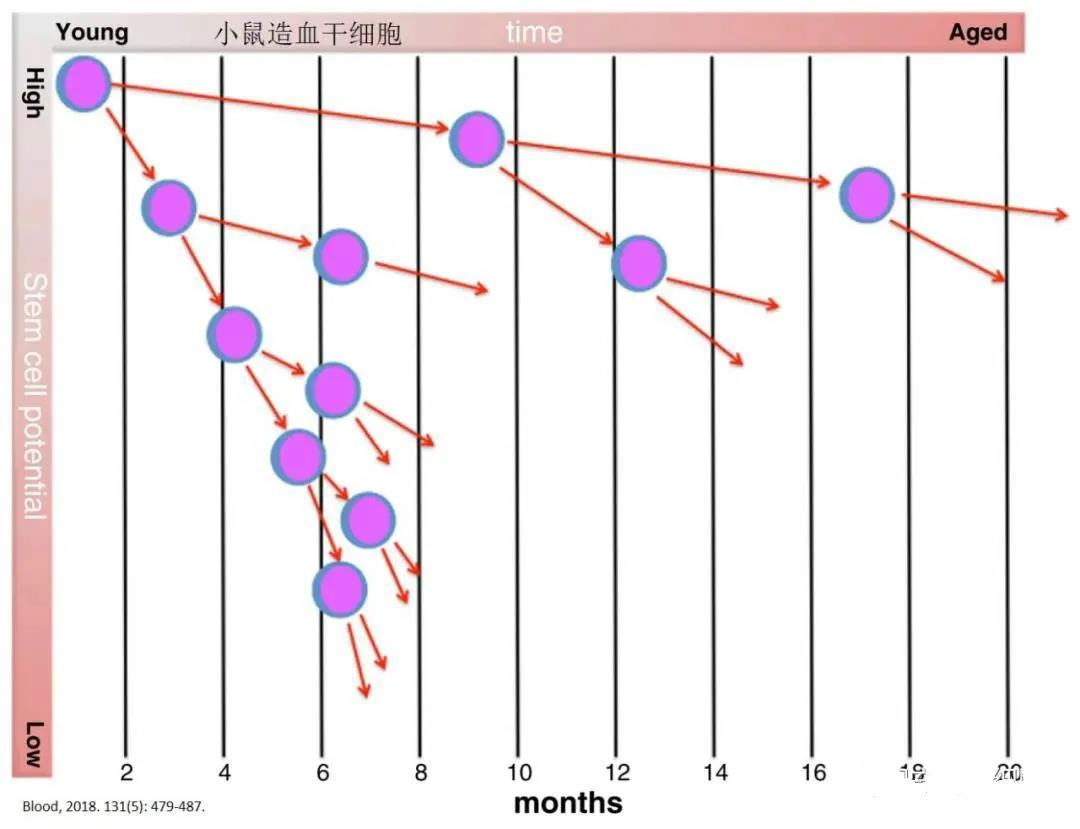

With each cell division, the potential of HSCs to differentiate into blood cells diminishes. At the same time, the number of progenitor hematopoietic cells—descendants with reduced differentiation capacity—increases, compensating for the loss of function in individual stem cells. As a result, the extensive proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells themselves can ultimately lead to their exhaustion. Conversely, maintaining a quiescent state helps preserve the functional integrity and youthful stemness of these vital cells.

In various chronic and stress-related physiological conditions, the absence of DNA-binding protein inhibitor 1 (Id1) can protect HSCs from exhaustion and promote their quiescence. Therefore, targeting Id1 may enhance the survival and functionality of HSCs during chronic stress and aging.

As age increases, the myeloid HSC population expands and eventually becomes dominant within the overall elderly HSC pool.

The aging of HSCs is primarily evident in the following aspects:

1. B cell production declines significantly with age, and the diversity of the B cell lineage also diminishes, accompanied by reduced antibody affinity and impaired class switching.

2. The production of new T cells also declines with age, partly due to thymus degeneration;

3. NK cells exhibit reduced cytotoxic activity and cytokine secretion;

4. Although the number of myeloid cells has increased, their functional capacity has declined—for instance, neutrophils exhibit reduced migration in response to stimuli, and macrophages show diminished phagocytic activity.

5. Late-stage red blood cell production also decreases.

In fact, young bone marrow cells show considerably poorer engraftment when transplanted into older recipients compared to their performance in younger recipients. Although both aged and young hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) released into circulation under granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) treatment exhibit similar mobilization effects, the bone marrow homing efficiency of aged HSCs is significantly reduced when these cells are intravenously transplanted into irradiated recipients. As a result, Donating bone marrow is not recommended for older adults. In transplantation studies, young HSCs consistently outperformed their older counterparts in terms of hematopoietic function. 。

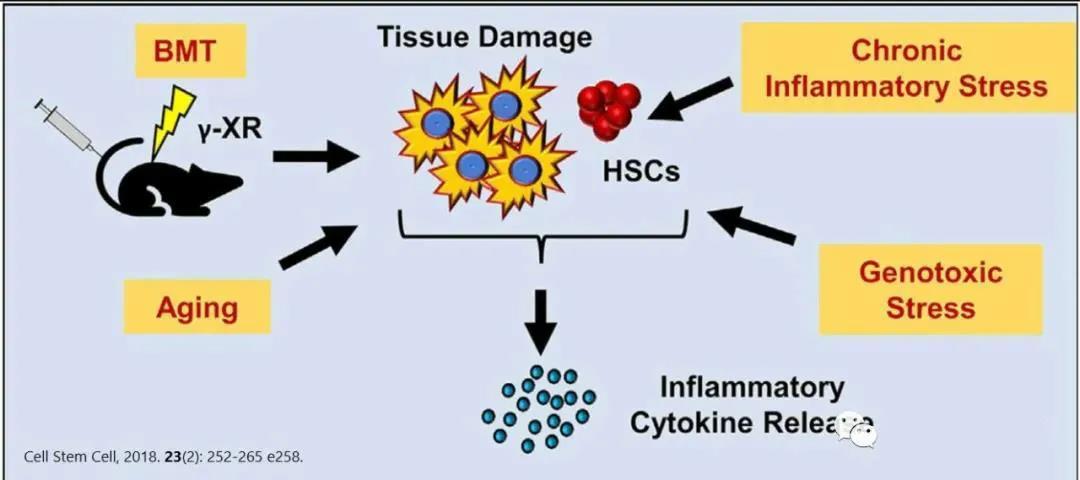

The most irreversible cause of HSC aging is linked to the accumulation of random DNA damage. Mice or patients with mutations in DNA repair-related protein-coding genes often exhibit hallmarks of premature aging in their hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Aging HSCs accumulate more DNA damage, likely due to elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the cells, which also trigger the production of genotoxic metabolic byproducts. Additionally, aged HSCs suffer from reduced DNA replication efficiency and transcriptional repression, a consequence of prolonged proliferative stress. While aging is traditionally thought to be primarily driven by the activation of p16—a key marker of senescent cells—some studies suggest that p16-mediated senescence has only a modest impact on maintaining homeostasis in aging HSCs.

High levels of ROS produced by mitochondria accumulate continuously in aging hematopoietic stem cells, ultimately impairing their function. Mitochondrial autophagy helps eliminate excess ROS, thereby reducing oxidative damage to mitochondria. Notably, a significant proportion of aged hematopoietic stem cells exhibit impaired autophagy levels—yet maintaining an adequate level of autophagic flux is crucial for preserving the youthful state of these cells.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and endothelial cells are the primary components of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche surrounding blood vessels, significantly influencing HSC proliferation, differentiation, and aging. During the aging process, the bone marrow microenvironment undergoes numerous cellular and structural changes, and these alterations in the extracellular matrix can fundamentally impact stem cell function.

As mentioned above, the aging of hematopoietic stem cells with advancing age leads to immune system senescence, characterized by diminished phagocytic activity of immune cells, altered cell migration patterns, and reduced capacity to produce specific antibodies. Clinically, these changes may increase the incidence and mortality rates among older adults by elevating susceptibility to infections, malignant tumors, and autoimmune disorders. Given that both inflammation and aging can heighten the risk of leukemia, targeting and eliminating unwanted inflammatory senescence factors emerges as a promising strategy to preserve HSC function and immune health, thereby preventing declines in hematopoiesis and the emergence of malignant clones.

Senescence of mesenchymal stem cells

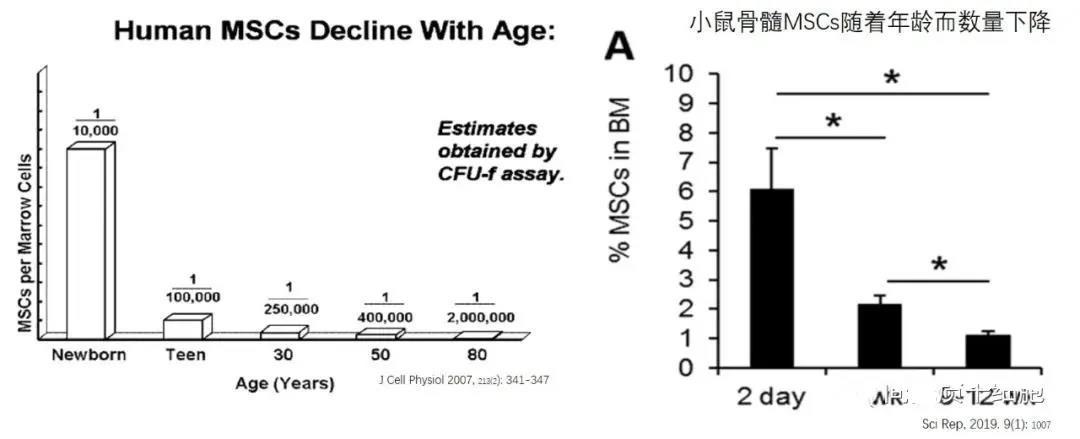

Once humans and mice are born, the levels of MSCs in their bone marrow steadily decline—despite the fact that bodily functions reach their peak during adolescence. For bone marrow MSCs, however, their "debut" marks the very moment of their greatest vitality!

Comparison of MSC Functions Across Different Age Groups

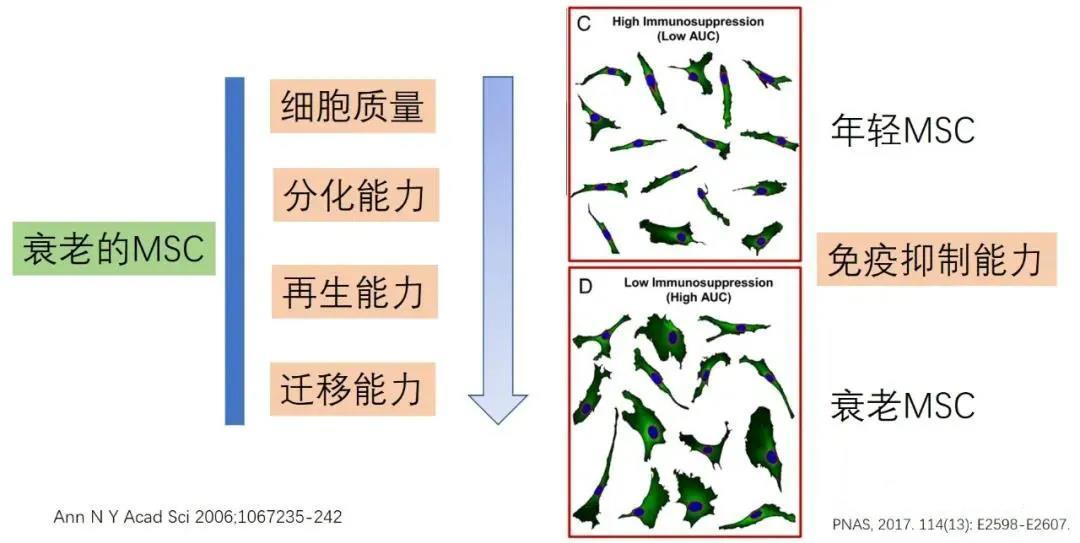

Compared to MSCs derived from young donors, mesenchymal stem cells from older donors exhibit significantly reduced proliferative capacity, with aged MSCs showing enlarged cell bodies due to senescence. Additionally, MSCs isolated from older donors display an increased number of SA-β-gal–positive cells—a marker of cellular aging. Moreover, the antioxidant ability of MSCs gradually declines as donor age advances. Age-related senescence also leads to decreased expression of several key membrane proteins in bone marrow-derived MSCs, including CD13, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD146, and CD166.

Interestingly, MSCs' ability to differentiate into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes is a fundamental characteristic of these cells—and it remains unaffected by age. Moreover, the efficiency of osteogenic differentiation doesn’t necessarily correlate with MSCs' broader multi-potential differentiation capacity.

Bone marrow MSCs derived from multiple donor sources exhibit individual variations in clonogenicity, cell size, proliferative potential, and immunosuppressive capacity. According to the clonal CFU-F assay, the number of bone marrow MSCs declines with age, impairing their ability to effectively promote the renewal of tissue progenitor cells. Additionally, adult bone marrow MSCs show a reduction in cell numbers, accompanied by increased levels of aging markers such as ROS, p21, and p53.

MSCs exhibit distinct age-related differences in cell proliferation, with aged or senescent MSCs showing declines in three key areas: cell quality, differentiation capacity, and migratory ability. Compared to cells isolated from young donors, aged MSCs also display additional hallmarks of cellular aging, such as reduced vitality, diminished proliferative potential, and impaired differentiation capabilities. Consequently, studies have shown that aged MSCs tend to deliver less effective clinical outcomes in therapeutic applications.

Obese individuals exhibit increased oxidative and metabolic stress in MSCs derived from adipose tissue, which directly impacts the mitochondria of these adipose-derived MSCs, leading to DNA damage, telomere shortening, reduced proliferation and stemness (manifested by decreased expression of NANOG, SOX2, and OCT4), as well as heightened apoptosis and cellular senescence.

Interestingly, the functional characteristics of adipose-derived MSCs isolated from different anatomical sites vary to varying degrees. Moreover, an obesogenic environment induces specific DNA methylation patterns, leading to changes in mitochondrial shape and number—and consequently affecting the functional properties of adipose MSCs. When co-cultured with young MSCs, macrophages exhibit markers characteristic of the M2 phenotype, such as Arg1 and IL-10, whereas macrophages co-cultured with aged bone marrow MSCs express TNF-α, a hallmark of the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. Additionally, age-related increases in adipogenesis may contribute to the SASP state, likely mediated by the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2 (PPAR-γ2) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (CCAAT/EBP).

BM-MSC-derived EVs from donors of different ages showed significant age-related differences in both their content and immunological characteristics. In a mouse model, extracellular vesicles (EVs) isolated from young MSCs contained higher levels of autophagy-related mRNA and sirtuins, enabling aged hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to regain functional capacity and vitality. In contrast, bone marrow MSCs from older donors released SASP, which promoted an inflammatory state in HSCs and ultimately impaired the function of younger HSCs.

MSC's age-related aging (senescence)

After undergoing a certain number of cell divisions, MSCs enter senescence, characterized morphologically by enlarged and irregular cell shapes, ultimately ceasing proliferation. Meanwhile, inappropriate culture conditions significantly accelerate this process. Aged MSCs exhibit reduced multipotency and impaired production of growth factors essential for tissue repair. Aging and oxidative stress significantly increase the miR-183-5p content in bone marrow-derived extracellular vesicles, leading to decreased cell proliferation, diminished osteogenic differentiation, and promoting MSC senescence by impairing heme oxygenase-1 (Hmox1) activity.

Aging MSCs exhibit reduced clonal formation and proliferative capacity, with a differentiation bias toward adipogenesis and diminished osteogenesis. Within the body, MSC senescence leads to reduced osteogenic capacity, contributing to age-related conditions such as osteoporosis. As a result, MSC aging is considered a key factor behind the impaired fracture healing observed with advancing age. This also partially explains why older adults are more prone to osteoporosis, as well as why fat cells accumulate in the bone marrow of elderly individuals.

Research indicates that autophagy is essential for maintaining the stemness and differentiation potential of stem cells, yet this process deteriorates during stem cell aging. As age advances, the autophagic function of bone marrow MSCs and osteocytes declines. Interestingly, activating autophagy can reverse the aging of bone marrow MSCs, restoring their osteogenic differentiation and proliferative capacity. Autophagy also helps protect MSCs from excessive oxidative stress; however, inhibiting autophagy actually mitigates the aging process in MSCs cultured over extended periods. Moreover, growing evidence suggests that exosomes secreted by MSCs possess the remarkable ability to rescue impaired autophagic function in damaged cells.

Current data on the relationship between autophagy and aging are partly contradictory: in fact, autophagy may both promote and inhibit aging, depending on the cellular environment and the type of stress involved.

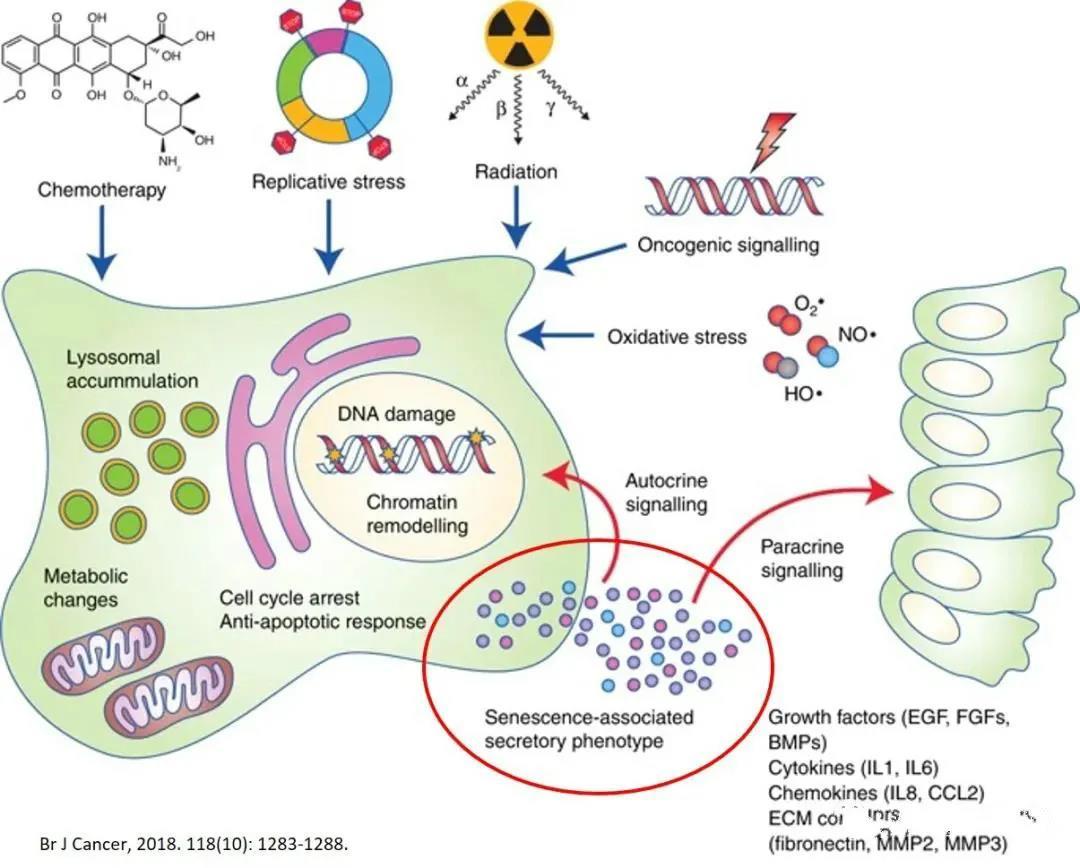

Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)

SASP is a novel mechanism that links cellular senescence to tissue dysfunction. Senescent cells secrete what are known as SASP factors, which sustain and amplify aging through autocrine/paracrine regulatory loops—impacting both the senescent cells themselves and their surrounding neighbors. In essence, SASP acts as a key mediator, transmitting the aging signal to adjacent cells and ultimately triggering devastating age-related diseases, while also contributing to persistent, low-grade chronic inflammation—a condition defined as "inflammaging." SASP exhibits a dynamic composition, comprising pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8), chemokines, growth factors, and proteases (including MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-10). The specific mix of these components varies depending on cell type, microenvironment, and the particular mechanisms driving cellular senescence.

Aging BMSCs enter a SASP state, leading to the excessive release of SASP-related exosomes, including IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, TIMP-2). These secreted molecules trigger systemic inflammatory responses, which in turn impair the immunomodulatory functions of MSCs and promote cancer progression. In vivo, aged bone marrow-derived MSCs exhibit enhanced adipogenic differentiation while showing reduced osteogenic potential. Simultaneously, they secrete exosomes containing miRNA-146a along with SASP factors, further stimulating macrophage polarization from the M2 to the M1 phenotype, thereby exacerbating inflammatory aging.

LC-MS/MS-based proteomic identification, followed by genomic analysis (GO), categorized the SASP components into four groups: extracellular matrix/cytoskeleton/cell junctions, metabolic processes, redox factors, and regulation of gene expression.

Aging and Inflammation: Inflammatory Aging

All types of substances produced by tissues and cells during live-cell turnover and metabolism—such as cellular debris, metabolites, incompletely degraded products, or those processed without enzymatic involvement—are collectively referred to as "molecular garbage."

To manage molecular waste and maintain homeostasis within the body, several adaptive strategies have been developed, such as recognizing PAMPs or MAMPs (microbe-associated molecular patterns), which can directly activate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and trigger downstream inflammatory cascades. In animals, a rescue mechanism known as "autophagy/mitophagy" also plays a crucial role in preventing the buildup of cellular debris. However, this process becomes impaired in inflammatory environments, often leading to disruptions in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and activation of DNA damage responses, among other issues.

Inflammation is a defensive mechanism that protects the body from harmful substances trying to invade and endanger life. Maintaining homeostasis is crucial during both childhood and adulthood, yet chronic inflammation serves as a common pathological foundation underlying age-related diseases such as cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease—and may also represent a significant risk factor contributing to the increased incidence and mortality rates of most degenerative conditions in older adults. Additionally, alterations in the tissue microenvironment, such as the accumulation of cellular debris and systemic changes in metabolic and hormonal signaling, can further fuel the progression of chronic inflammation. Importantly, cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage play a pivotal role in responding to these age-associated changes, ultimately driving the development of chronic inflammatory diseases.

Most age-related diseases are caused by common and interdependent conditions, including: Chronic inflammation, organelle dysfunction, stem cell impairment, and the accumulation of senescent cells In animal models, genetically or pharmacologically eliminating senescent cells can extend lifespan and delay the onset of age-related pathologies. At the cellular level, senescence may trigger inflammation. As organisms age, accumulated senescent cells in tissues secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines—known as the "senescence-associated secretory phenotype" (SASP)—which contribute to the development of chronic inflammation.

Therefore, inflammation has long been recognized as a driving force behind the development of cancer in many tissues. That’s why it’s crucial to eliminate chronic inflammation from the body!

Summary at the end

Longevity is humanity's ultimate goal, and achieving it means fighting against aging.

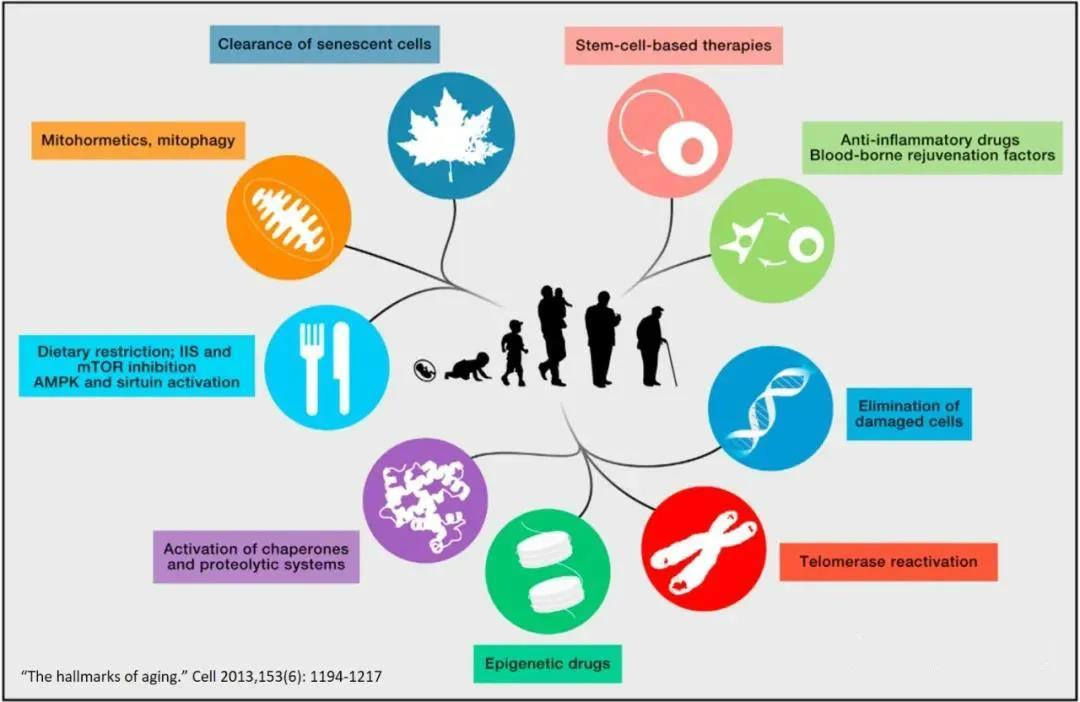

Articles highlight that there are currently nine anti-aging (anti-senescence) interventions: stem cell therapy, anti-inflammatory drugs and youthful serum factors, strategies to reduce damaged cells, boosting telomerase activity, epigenetic therapies, activating the body’s surveillance and protein degradation systems, calorie restriction, mitochondrial autophagy, and the elimination of senescent cells.

The aging of MSCs within the body is considered a partial reason for the decline in tissue and organ function as the organism ages. Compared to young mice, an aging environment can suppress the function and potential of adult stem cells. Hyaluronic acid polysaccharides coated on cell culture surfaces help maintain the differentiation potential of human MSCs, enhance their proliferative capacity, stimulate telomerase activity, and delay cellular aging.

Therefore, the high hyaluronic acid content in the human body can serve as an initial indicator of the aging status of MSCs within the body. As people enter middle age, especially when hyaluronic acid levels in the subcutaneous layer decline, it not only leads to the appearance of skin wrinkles but also signals that MSCs throughout the body are gradually aging.

Fortunately, infusing healthy MSCs can help slow down the body's aging process. MSCs may detect mitochondria released by damaged somatic cells and subsequently mount a targeted response, initiating an adaptive repair mechanism that helps these cells recover. Moreover, fragments of healthy MSCs can be engulfed by the body’s immune cells, promoting the polarization of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 type to the anti-inflammatory M2 type. Additionally, apoptotic bodies generated when infused MSCs undergo apoptosis in vivo stimulate the proliferation and renewal of endogenous MSCs, helping to restore youthful vitality to MSCs in the bone marrow. While the key regulators of MSC aging remain largely unidentified, they hold significant potential as therapeutic targets for combating age-related diseases and halting overall bodily senescence.

Interestingly, menopause and oophorectomy lead to a mild systemic inflammatory state and elevated plasma chemokine levels, while estrogen therapy helps suppress this condition. Therefore, for women, maintaining healthy, well-functioning ovaries is crucial. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can also help preserve ovarian function—and even offer a potential treatment for infertility caused by premature ovarian failure.

Related News