Can stem cells help people quit drugs? Do you believe it?

2021-06-28

People often say: "Once you take drugs, you’ll spend the rest of your life trying to quit. One taste of drugs can lead to lifelong regret." Drugs severely harm both physical and mental health, consuming not only the body but also the soul—and ultimately destroying the very essence of our beautiful lives. Scenes from popular TV series like *Operation Mekong* and *Operation Icebreaker* deeply resonate with audiences, yet the reality is undoubtedly far more horrifying than what these shows portray. The dangers of drugs are far greater than we could ever imagine.

In our country, the drug situation is experiencing a dangerous resurgence and spreading rapidly, with a growing number of people using drugs. Once someone becomes addicted, breaking free from addiction is already extremely challenging—and more than 95% of those who have successfully detoxed end up relapsing within just six months. Even more alarming is that the majority of drug users in China fall within the 15- to 30-year-old age group, including a significant number of teenagers. [1] 。

The dangers of drug abuse are significant.

It is well known that drug abuse poses significant harm to the human body, primarily manifesting in the following ways: [2] :

Damage to the nervous system: Drugs cause significant harm to both the central and peripheral nervous systems, leading to abnormal effects such as excessive stimulation or inhibition, and resulting in a range of neurological and psychiatric symptoms. Autopsy findings also reveal that pathological changes in the nervous system include widespread astrocyte lesions, extensive brain swelling and degeneration, progressive alterations in the globus pallidus, necrosis of spinal gray matter, chronic inflammatory and degenerative changes in peripheral nerves.

Damage to the cardiovascular system: Drug use, especially intravenous injection, can introduce impurities from illicit substances and contaminated needles, leading to a range of cardiovascular disorders such as infective endocarditis, arrhythmias, thrombophlebitis, vascular embolism, and necrotizing vasculitis. Many drugs exert direct toxic effects on the cardiovascular system, severely impairing users' myocardial contractility, cardiac reserve, and physical endurance. For instance, cocaine can trigger vasoconstriction, coronary artery spasm, and even myocardial infarction. Moreover, cocaine may also accelerate the progression of coronary atherosclerosis.

Damage to the respiratory system: When drugs are consumed via smoking or inhalation, they come into direct contact with the respiratory tract's mucous membranes. Meanwhile, intravenous drug use exposes the lungs’ delicate capillary network to the substances, significantly increasing the risk of respiratory conditions such as bronchitis, pharyngitis, lung infections, embolism, and pulmonary edema. Drug abuse can severely damage the respiratory system through three primary mechanisms: the direct irritant effects of illicit substances on the airways; the specific toxic impact of drugs entering the body via various routes; and the secondary consequences of malnutrition and infections often triggered by substance use, which may also compromise respiratory health.

Damage to the digestive system: Drug-induced appetite suppression not only leads to physical wasting but can also result in deficiencies of essential vitamins and minerals, triggering a range of malnutrition-related syndromes. Drug use frequently slows down gastrointestinal motility, leading to constipation and even intestinal obstruction. In opioid addicts who abruptly stop using drugs, sudden acceleration of gastrointestinal motility may occur, causing severe abdominal pain and diarrhea. Meanwhile, cocaine exerts potent vasoconstrictive effects on blood vessels throughout the body; prolonged and intense constriction of intestinal blood vessels can lead to intestinal ischemia and tissue necrosis.

Damage to the reproductive system: Long-term drug use can lead to diminished sexual function, potentially resulting in complete loss of sexual capability. In men, this may manifest as erectile dysfunction or impotence; in women, it can cause menstrual irregularities, leading to infertility and amenorrhea. Research conducted abroad on the genetic effects of opioids on adult lymphocytes revealed that heroin addicts have a chromosomal damage rate five times higher than that of healthy individuals. Moreover, DNA repair defects persist even one year after detoxification.

Harm to infants: Drug use during pregnancy allows substances to cross the placenta from maternal blood into the fetal bloodstream, with detectable levels typically appearing in the fetus within about 1 hour. When mothers use opioid drugs during pregnancy, 60% to 90% of newborns delivered will exhibit withdrawal symptoms of varying severity. Neonatal abstinence syndrome not only increases the risk of early complications in newborns—such as hypoglycemia, birth asphyxia, and developmental abnormalities—but can also lead to life-threatening respiratory failure in moderate to severe cases. Even among survivors, these infants face a sudden infant death risk that is 5 to 10 times higher than that of full-term babies born to non-addicted mothers. Additionally, infants born to mothers addicted to methadone may experience neonatal withdrawal symptoms in up to 94% of cases.

Drug use leads to AIDS. The HIV virus is present in the blood, breast milk, semen, and vaginal fluids of infected individuals or patients, and its primary modes of transmission include: bloodborne transmission, sexual contact, and mother-to-child vertical transmission. When drug users inject drugs intravenously, sharing or using contaminated needles directly facilitates the spread of the virus through blood.

Drug use triggers hepatitis C virus infection. Injecting drugs has been identified as a synergistic factor in both HCV infection and disease progression, significantly increasing the incidence and mortality rates associated with HCV. Currently, it remains unclear how drug abuse diminishes the antiviral effects of interferon against HCV infection.

Why do people repeatedly use drugs?

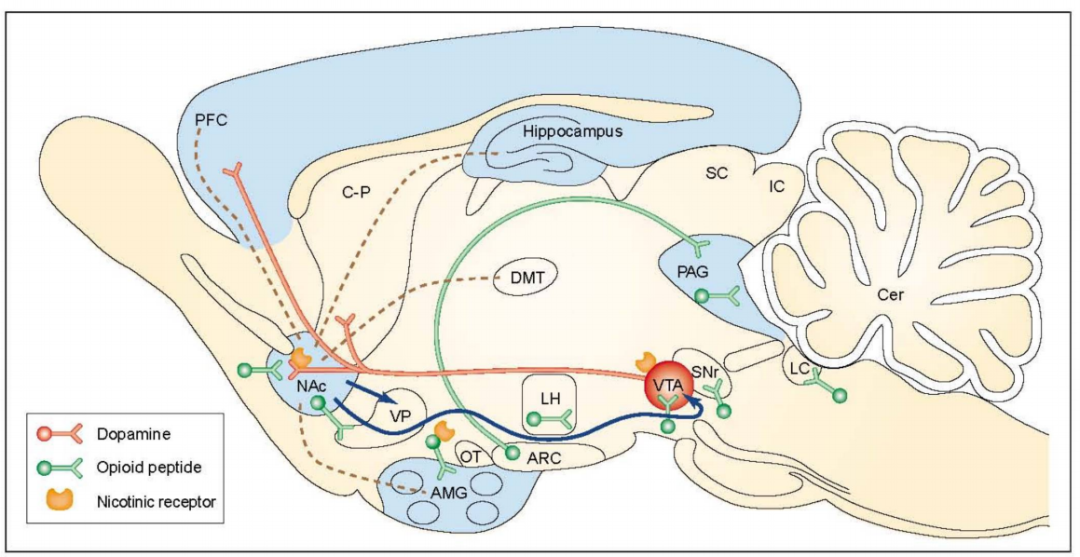

Why do people turn to drugs? Why does drug use lead to addiction? And once someone becomes addicted, why is it so hard to break free? Even after successfully quitting, why do many relapse so quickly? What exactly are the mechanisms behind these complex processes? These questions have captivated researchers around the globe. For decades, the fact that major addictive substances like opioids and ethanol can induce both physical dependence and addiction has left us puzzled about the very nature of drug addiction. However, by the 1970s and 1980s, researchers discovered a groundbreaking link: drug abuse-driven addiction shares common neural and cytokine networks with memory formation. Remarkably, this same neural molecular network relies on CREB activation to regulate multiple signaling pathways—processes that ultimately drive and reinforce both the acute rewarding effects and the chronic dependency characteristic of addiction. [3] The neural circuitry is established (as shown in Figure 1).

Currently, the most well-known brain reward circuit involves dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain and their projection targets in the limbic forebrain, particularly the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the prefrontal cortex. [4] In fact, the VTA-NAc pathway serves as a key site where nearly all addictive drugs produce their acute reward effects. This involves two primary mechanisms: First, all substances of abuse can enhance dopamine-mediated transmission in the nucleus accumbens, albeit through vastly different mechanisms; and second, certain drugs can also directly influence nucleus accumbens neurons via dopamine-independent pathways.

Figure 1: The key neural circuitry of addiction. Marginal afferents to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) are shown as brown dashed lines. Blue arrows indicate NAc efferents, which are thought to play a role in drug reward. Projections from the mesolimbic system—considered a critical substrate for drug reward—are highlighted in red. This system originates in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and includes projections from the NAc and other limbic structures, such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the ventral domain of the caudate-putamen (C-P), the olfactory tubercle (OT), and the amygdala (AMG)—though the OT and AMG projections are not depicted here. Neurons containing opioid peptides, involved in the rewarding effects of opioids, ethanol, and nicotine, are shown in green. These opioid systems encompass both local brain enkephalins (short segments) and hypothalamic-mesencephalic endorphins (long segments). The distribution of GABA_A receptor complexes is indicated by a light blue area, suggesting it may be a crucial component of ethanol reward pathways. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, believed to reside on neurons expressing dopamine or opioid peptides, are also illustrated. Abbreviations: Arc, arcuate nucleus; Cer, cerebellum; DMT, dorsal thalamus; Hypo, hypothalamus; LC, locus coeruleus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; PAG, periaqueductal gray; SC, superior colliculus; SNr, substantia nigra reticulata.

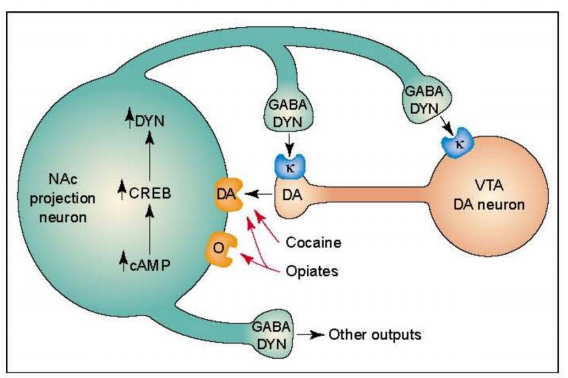

The evolutionary understanding of how drug abuse affects the VTA-NAc pathway represents a major advancement in the field (as shown in Figure 2). It provides critical neurobiological insights into the mechanisms underlying drug addiction. [5-6] Neurons containing dopamine regulate responses to food. [7] And drug abuse [8] Behavioral responses, dating back to the evolutionary origins of worms and flies, underscore the primordial power of this reward circuitry. This also helps direct researchers' attention toward potential neural sub-strategies—specifically, how compulsive behaviors driven by non-drug rewards may contribute to conditions like pathological overeating, problematic gambling, and sex addiction. Recent studies have further revealed that these same brain reward regions are linked to motivation deficits and impaired control in depression. [9] 。

Figure 2: Regulation of cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB) by Drug Abuse. The figure illustrates dopamine (DA)-containing neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which innervate a population of GABAergic projection neurons in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). These NAc neurons express dynorphin, and DYN plays a crucial role as a negative feedback regulator within this circuit. Specifically, DYN released from NAc neuron terminals binds to kappa opioid (k) receptors located on both the terminals and cell bodies of DA-containing neurons, thereby inhibiting their activity. Chronic exposure to drugs such as cocaine or opioids—and potentially other abused substances—can enhance this negative feedback loop by upregulating the cAMP signaling pathway. Activation of the cAMP pathway, in turn, stimulates CREB and promotes the synthesis of DYN. Abbreviations: O, opioid receptor.

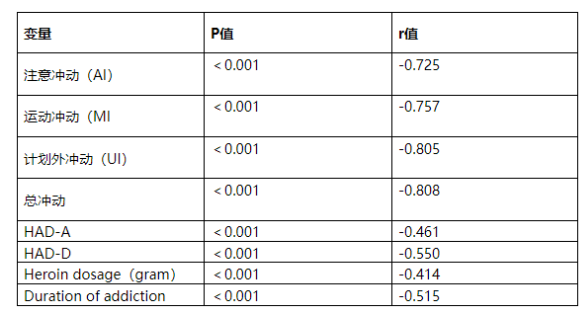

Another study titled "Serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels and impulsivity in heroin addiction: a cross-sectional, case-control study of 129 heroin addicts" reveals that GDNF, a neurotrophic factor that influences the dopaminergic system, plays a critical role as a target molecule in the treatment of heroin addiction. [11] Serum GDNF levels are associated with daily heroin dosage and the duration of addiction. Studies show that heroin addicts exhibit significantly higher total impulsivity scores, as well as elevated scores on the AI, MI, and UI subscales—these findings are negatively correlated with serum GDNF levels. Additionally, GDNF may also play a role in the genetic susceptibility to other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia. [12] ; GDNF has also been found to influence synaptic and structural plasticity. [13] This kind of plasticity change may lead to drug abuse and addiction.

Table 1: Factors Influencing Serum GDNF Levels in Heroin Addicts.

Existing drug addiction treatments deliver unsatisfactory results.

Currently, the primary drug-abuse treatment methods used in China include non-pharmacological approaches—such as cold turkey therapy, acupuncture, and surgical interventions—as well as pharmacological methods like tapering, substitution therapy, neuroleptic-induced hibernation, and traditional Chinese medicine treatments. However, extensive practical experience has revealed several limitations: First, while Western medications offer relatively good detoxification results, they often lead to difficult recovery processes and are too expensive for widespread use. Second, traditional Chinese medicine, though effective in some cases, tends to work more slowly and is less successful in managing acute withdrawal symptoms—particularly when dealing with severe or complex addictions. Finally, none of these methods have proven capable of effectively addressing the critical issue of relapse. As a result, identifying a treatment strategy that ensures complete physical detoxification has become a global challenge requiring urgent breakthroughs.

Today, as research into the molecular and cellular mechanisms of addiction continues to advance, scientists have identified molecular targets for nearly all major drugs of abuse—and have discovered that every drug-abuse target studied so far is a protein involved in synaptic transmission (though different drugs influence distinct neurotransmitter systems). [3-6] This discovery leads researchers to wonder: Could coordinated changes in multiple proteins, signaling pathways, and neurotrophic factors across various brain regions be achieved by reshaping synapses? Under today’s scientific and technological advancements, only stem cells offer a viable solution. But how exactly do stem cells help in addiction treatment?

Stem cells influence functional changes in multiple brain regions by coordinating signals across various targets.

On September 17, 2018, the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering published "Genome-edited skin epidermal stem cells protect mice from cocaine-seeking behavior and cocaine overdose." [10] This article in the present report provides key evidence demonstrating that engineered skin transplantation can effectively deliver BChE in vivo, thereby preventing cocaine-seeking behavior and overdose.

To determine whether implanting cells expressing hBChE could influence cocaine-induced drug-seeking behavior, researchers transplanted hBChE-expressing cells into GWT mice previously exposed to cocaine. Ten days post-transplantation, extinction training and drug-induced reinstatement were conducted. Following the initial cocaine injection, a pre-existing cocaine-associated preference was restored in the cocaine-primed GWT mice (as shown in Figure 3c), but this recovery did not occur in ethanol-primed CPP mice (Figure 4b). These findings suggest that skin-derived hBChE can effectively and specifically disrupt cocaine-induced addiction and memory formation. Meanwhile, ELISA assays confirmed that hBChE levels in the blood of GWT mice receiving hBChE-expressing cell implants remained elevated, with stable expression persisting in vivo for over 8 weeks (Figure 4g). Their results highlight the potential clinical significance of future skin-based gene delivery strategies for treating cocaine abuse and overdose.

Figure 3: Implantation of cells expressing hBChE reduces cocaine-induced locomotion and protects against cocaine overdose. a, Skin organoids derived from either control or hBChE-expressing cells were generated and transplanted into host mice. Prior to implantation, the cells were infected with a lentivirus encoding firefly luciferase for in vivo imaging of the transplanted skin. b, Histological analysis of transplanted skin tissue collected from mice grafted with hBChE skin organoids (GhBChE), compared to control mice (GWT). Scale bar, 50 μm. c, Detection of hBChE levels in blood samples via ELISA, measured 10 weeks post-implantation using specific antibodies targeting Krt10, an early marker of epidermal differentiation. Each group consisted of 5 mice. Mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of 10 mg/kg cocaine (n = 6 per group). Data are presented as mean ± standard error. A two-compartment pharmacokinetic model was established to characterize the cocaine concentration-time profile in the nucleus accumbens. Additionally, changes in dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens following intraperitoneal administration of cocaine were monitored. Mice receiving 10 mg/kg cocaine (n = 6 per group) showed distinct behavioral responses. Individual animal trajectories were plotted, revealing significant treatment × time interactions: F(6,70) = 6.549, P < 0.0001, as determined by two-way ANOVA. d, Cocaine-induced motor activity in GhBChE and GWT mice (GWT: n = 11; GhBChE: n = 8). Nonlinear dose-response curves were fitted to illustrate the relationship between cocaine dosage and its effects on motor performance. e, Total distance traveled by mice after intraperitoneal administration of 0, 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg cocaine. Treatment × dose interaction was highly significant: F(3,68) = 11.83, P < 0.0001, as confirmed by two-way ANOVA. f, Number of grooming episodes observed in mice following administration of 0, 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg cocaine via intraperitoneal injection. Treatment × dose interaction reached statistical significance: F(3,65) = 6.223, P = 0.0009, again supported by two-way ANOVA. g, Mortality rates observed in GhBChE and GWT mice after intraperitoneal injections of escalating doses of cocaine: 40, 80, 120, and 160 mg/kg. Each experiment involved 8 animals per test group across 3 independent trials.

Figure 4: Implantation of hBChE-expressing cells attenuates cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) acquisition and reinstatement. a) After implantation, GhBChE and GWT mice underwent a pre-test session with cocaine on Day 1, followed by conditioning sessions (Days 2–5) and the CPP expression test on Day 6. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 9 per group; treatment × day interaction was analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA: F1,16 = 5.04, P = 0.039). Post-hoc significance was assessed via Fisher’s least significant difference test. A significant difference was observed between the pre-test and expression test sessions (*P = 0.016). b) Following implantation, GhBChE and GWT mice were subjected to a pre-test session on Day 1, ethanol conditioning over Days 2–5, and the CPP test on Day 6. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 8 per group; repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant treatment × day interaction: F1,14 = 0.084, P = 0.76). c) On Day 1 (pre-test), mice exhibited similar levels of cocaine-induced CPP following cocaine conditioning on Day 6. On Day 7, they underwent transplantation surgery. Ten days post-recovery, both GhBChE and GWT mice were extinguished and remained in extinction until Day 31. On Day 32, the mice were re-challenged with cocaine, and CPP was measured again. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 8 per group; treatment × day interaction was analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA: F3,42 = 12.45, P = 6 × 10⁻⁶). Post-hoc analysis using Fisher’s least significant difference test confirmed statistical significance. **P = 0.00013, indicating a significant difference between the most recent extinction and the reinstatement extinction phase. d) After the pre-test on Day 1 and ethanol conditioning on Day 6, mice displayed comparable levels of ethanol-induced CPP. They then underwent skin grafting surgery on Day 7 and remained in extinction until Day 27. On the recovery day (Day 28), the mice were administered ethanol, and CPP was recorded. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 8 per group; treatment × day interaction was analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA: F3,42 = 0.0574, P = 0.98).

The study demonstrates that genome-edited skin stem cell transplantation can be used for long-term, in vivo delivery of active cocaine hydrolase, offering a therapeutic opportunity to address cocaine abuse—or even co-abuse with other substances—beyond just the drug itself. Meanwhile, skin grafting procedures, including methods based on culturing autologous epidermal grafts derived from human epidermal stem cells, have already been clinically applied for decades in the treatment of burn injuries. [14-16] Engineering skin stem cells and cultured epidermal autografts have also been used to treat other skin conditions, including vitiligo and genetic skin disorders such as epidermolysis bullosa. [17-18] These regenerative skin grafts are stable and have demonstrated long-term survival in clinical follow-up studies. [15-18] For cocaine addicts and individuals at high risk of cocaine abuse who are seeking help or treatment, a skin gene therapy featuring hBChE expression can address several critical aspects of drug misuse, including reducing the development of cocaine-seeking behaviors, preventing the relapse into drug-seeking activities triggered by cocaine exposure, and even safeguarding against cocaine overdoses following skin transplantation—potentially rendering them "immune" to further cocaine abuse.

Drug addiction has become an inescapable issue in our lives. Combining stem cell therapy with existing treatment methods—leveraging their respective strengths while minimizing weaknesses—could make it a powerful new tool for overcoming addiction. We believe that, as science and technology continue to advance and with humanity’s relentless dedication, one day we will ultimately conquer drugs altogether. Let us always remember: A drug-free world is the most beautiful vision of all.

Related News