Did you know that what’s quietly slipping away isn’t just time—it’s also your muscle mass?

2021-02-07

Growing old and losing strength may seem like an irresistible natural law. After entering middle age, people often start paying close attention to health issues such as osteoporosis and obesity—but there’s another critical concern that many might be overlooking: our muscles.

Human muscle mass peaks around age 30, after which it gradually declines. In middle age, this loss often goes unnoticed, but once we enter old age, the rate of muscle decline accelerates dramatically. As a result, many seniors find themselves struggling to walk, unable to pick up objects—or even open bottle caps, wring out towels, or manage daily tasks with ease. They also tend to feel more fatigued and fall ill more frequently. What used to be dismissed as inevitable signs of aging may, in fact, be largely caused by "muscle loss."

"Muscle loss" was originally defined as the decline in muscle strength caused by the gradual loss of skeletal muscle with age. Today, it’s often used to describe the process of muscle cell damage, which includes changes in the microenvironment, heightened inflammation, impaired mitochondrial and DNA function, and unfavorable outcomes for stem cell homing. Clinically, this manifests as reduced muscle strength, diminished mobility and functional capacity, increased fatigue, metabolic disturbances, and a higher risk of falls and fractures. This phenomenon is particularly common among older adults: it’s estimated that about 5% of individuals aged 60 to 70 already suffer from sarcopenia, while this figure rises to 11% among those aged 80 and older.

01 Why does muscle mass decrease?

Muscle loss can ultimately be attributed to just four main factors.

Alterations in the skeletal muscle microenvironment

Changes in chemokine levels: It is well known that tissues and organs often contain stem cells, which can replicate in an orderly manner and replace cells lost due to aging or injury. Numerous pieces of evidence indicate that the ability of stem cells to migrate to damaged areas depends critically on the proper guidance provided by "signaling molecular pathways."

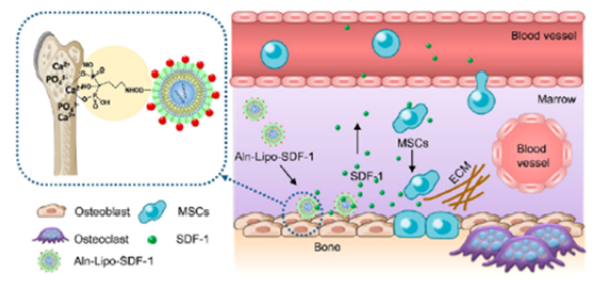

Among these, CXCR4/SDF-1 plays a critical role in the entire homing process of chemokine-driven hematopoietic stem cell migration to the bone marrow, including adhesion to bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells, transendothelial migration, and subsequent attachment to bone marrow stromal cells. Notably, CXCR4 and SDF-1 are regulated jointly at multiple levels—such as by factors like age, inflammation, hypoxia, and receptor dysfunction—highlighting the complex interplay of external cues in modulating this process.

Growth factor deficiency: Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) are well-known regulators and promoters of bone tissue formation, remodeling, and skeletal muscle protein synthesis. They modulate the proliferation, differentiation, and fusion of skeletal muscle precursor cells, playing a dual role in both skeletal muscle development and apoptosis.

Increased inflammatory factors: In chronic inflammation associated with muscle loss, protein degradation in muscle cells accelerates while synthesis declines. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is the primary mechanism driving protein breakdown in skeletal muscle cells. Various inflammatory factors—such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6)—as well as hormones like cortisol and angiotensin, and reactive oxygen species, can all contribute to the loss of myonuclei in skeletal muscle cells, leading to further depletion of muscle fibers and, ultimately, the development of sarcopenia.

Decline in the function of skeletal muscle mitochondria and DNA

As people age, skeletal muscle mitochondria and DNA experience functional decline. In muscles with severe atrophy, mitochondrial abnormalities occur more frequently, contributing to skeletal muscle cell apoptosis and impaired metabolic function. Moreover, changes in mitochondrial structure can disrupt the electron transport chain, compromising the muscle cells' ability to carry out normal aerobic respiration and ultimately leading to diminished skeletal muscle function.

Age-related protein balance is disrupted.

Skeletal muscle is characterized by a dynamic balance between protein synthesis and degradation within the cellular environment—only when the rates of synthesis and breakdown remain in equilibrium can muscle mass be maintained. However, with advancing age, aging triggers mechanisms that enhance protein synthesis while simultaneously boosting the expression of inflammatory factors, thereby counteracting the increased protein degradation to preserve this delicate balance. When this equilibrium between protein synthesis and breakdown is disrupted, the quality of muscle proteins begins to deteriorate, ultimately leading to skeletal muscle loss and functional decline.

Age-related decline in skeletal muscle stem cells and impaired homing

The alteration of the microenvironment serves as the initiating factor for stem cell homing. Following tissue injury, local areas express a variety of signaling molecules, including chemokines, adhesion factors, and growth factors. Each distinct microenvironment secretes unique sets of these signals, guiding stem cells to migrate directionally toward the injured tissue. Ultimately, stem cells home to the bone marrow, as well as to various organs, inflammatory sites, trauma locations—even specifically targeting tumor regions.

As people age, skeletal muscle tissues exhibit a decline in the local expression of various chemokines (such as SDF and CXCL12) and growth factors (like PGE2 and IGF-1), while inflammatory cytokines (including TGFα and IL-6) become elevated. This imbalance fosters a pathological inflammatory response that progressively accumulates within the microenvironment. Such chronic inflammation not only reduces the number of skeletal muscle stem cells but also impairs their functional capacity, ultimately leading to impaired muscle tissue regeneration and functional deficits.

02 How to Rebuild Lost Muscle?

The groundbreaking studies published in the prestigious academic journal *Science*—titled "Inhibition of prostaglandin-degrading enzyme 15-PGDH rejuvenates aged muscle mass and strength" and "Inhibition of the prostaglandin-degrading enzyme 15-PGDH potentiates tissue regeneration"—offer promising insights into how we might keep muscles young and strong.

These two articles highlight a key regulator of tissue repair called 15-PGDH, a prostaglandin-degrading enzyme. By boosting levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in tissues, 15-PGDH can stimulate the expression of chemokines such as CXCL12 and SDF, ultimately accelerating stem cell homing and activating endogenous tissue stem cells to repair damaged muscle tissue. This approach represents a groundbreaking, cell-level strategy for regenerating and repairing skeletal muscle—offering a potential solution to the critical issue of "muscle loss."

Research has shown that: 1. Inhibiting prostaglandin-degrading enzymes leads to changes in the skeletal muscle microenvironment—specifically, increased expression of chemokines and growth factors, along with reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines. 2. After inhibiting prostaglandin-degrading enzymes, there is a significant increase in the number of mitochondria in skeletal muscle. 3. Inhibition of these enzymes enhances protein synthesis within skeletal muscle fibers, resulting in notable improvements in muscle mass and function. 4. Moreover, inhibiting prostaglandin-degrading enzymes boosts the homing efficiency of both skeletal muscle stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells.

Stem cells, a class of multipotent cells with the remarkable ability to self-replicate and differentiate, can transform into various types of tissue cells under specific conditions—effectively replacing aging or dying cells. This makes them exceptional players in tissue regeneration and repair. Perhaps in the near future, stem cells will emerge as a groundbreaking new approach to reversing "muscle loss."

Related News