Where do stem cells go after being introduced into the body?

2020-07-14

TNF-α and IL-1β first stimulated MSCs (for 24 hours), after which the MSCs were locally injected into the cardiac chambers. Compared to the control group, MSCs pretreated with TNF-α and IL-1β showed a significantly increased number of cells that migrated toward the myocardial ischemia area, demonstrating that TNF-α and IL-1β enhance the adhesive capacity of MSCs. However, this effect was completely blocked by the monoclonal antibody against VCAM-1.

This article primarily elaborates on the distribution and metabolism of mesenchymal stem cells after they are introduced into the body.

First, it’s important to recognize that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and chemical drugs have distinct differences—ranging from, but not limited to,

① Chemical drugs are dead, while MSCs are alive; ② Chemical drugs have a well-defined half-life, whereas MSCs haven’t yet been shown to have one; ③ Chemical drugs target specific, single sites, while MSCs exert their effects through multiple, diverse pathways; ④ Chemical drugs rely entirely on passive transport within the body, whereas MSCs possess the unique ability to actively migrate toward chemical signals; ⑤ Chemical drugs exhibit excellent uniformity, but MSCs show poor consistency, with cells progressing through the cell cycle in a less synchronized manner.

What do these differences imply for clinical treatment? In clinical research or practice, is it appropriate for researchers to habitually approach cells using the same mindset they apply to chemical drugs?

Extensive experimental data have demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cells, once introduced into the body, do not persist long-term and are gradually cleared by the organism over time. This observation also suggests that the primary mechanism of action for mesenchymal stem cells does not involve their differentiation into tissue-specific mature cells. Animal studies reveal that in animals with a fully functional immune system, the clearance of intravenously administered MSCs occurs more rapidly, whereas in immunocompromised hosts, the elimination process slows down significantly. Moreover, the route of MSC administration plays a critical role in determining how long these cells remain in the body—local tissue injections, peripheral intravenous infusions, and arterial injections all markedly influence the retention time of MSCs within the organism. The following sections will provide a detailed discussion on this topic.

Local injection

Common sites for local MSC injections include the brain, limb muscles, heart, liver, and lumbar spine (subarachnoid space).

After locally microinjecting human bone marrow-derived MSCs into the striatal region of rat brains, the presence of these cells was still detectable after 72 days. Moreover, the MSCs were observed to migrate toward the corpus callosum and cerebral cortex. When MSCs were injected locally into the right caudate nucleus of the brain, their presence could be detected in multiple brain regions as early as 4 weeks later, with a clear preference for migration along the course of blood vessels. In contrast, when MSCs were administered via carotid artery injection, their survival in the brain typically lasted only 1–2 days. When iron-oxide–labeled bone marrow MSCs were injected into the carotid artery of rats subjected to a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, 24 hours later, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that these cells had successfully crossed the blood-brain barrier and migrated to various brain areas, including the cerebral cortex, subcortical white matter, striatum, and brainstem. Notably, MSCs were even found to migrate to the contralateral side of the brain. Interestingly, when rats received either human bone marrow MSCs or rat bone marrow MSCs via carotid artery injection, the human MSCs were cleared from the body significantly faster than the rat MSCs. This suggests that the host organism efficiently eliminates cells of foreign species at a quicker rate compared to its own cells.

TNF-α and IL-1β first stimulated MSCs (for 24 hours), after which the MSCs were locally injected into the cardiac chambers. Compared to the control group, MSCs pretreated with TNF-α and IL-1β showed a显著 increased number of cells that migrated toward the myocardial ischemia area, demonstrating that TNF-α and IL-1β enhance the adhesive capacity of MSCs. However, this effect was completely blocked by the monoclonal antibody against VCAM-1.

Whole-body injection

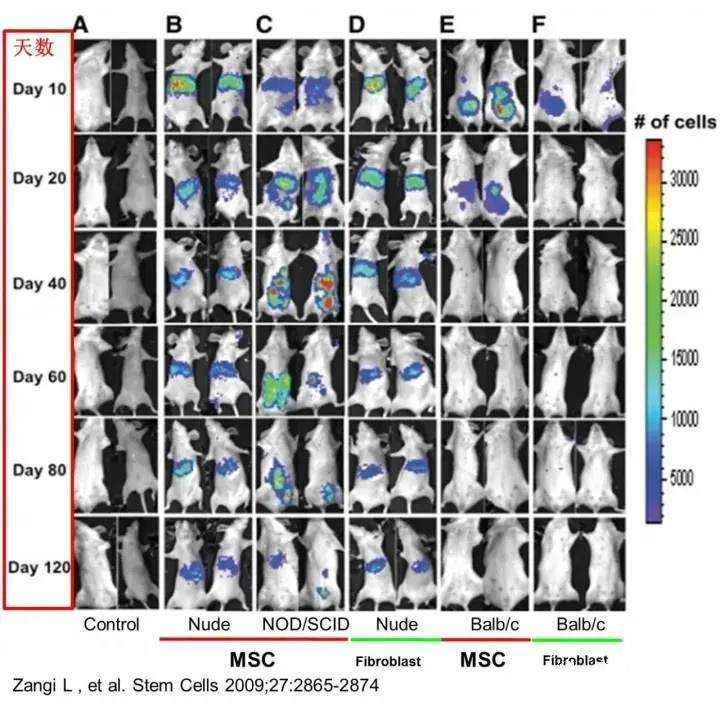

After intraperitoneal injection into immunodeficient mice (nude mice and NOD/SCID mice), MSCs persisted in multiple tissues and organs of the body for up to 120 days. In contrast, MSCs survived for just over 20 days in immunocompetent, allogeneic mice, but could remain viable for more than 40 days in syngeneic mice (see figure).

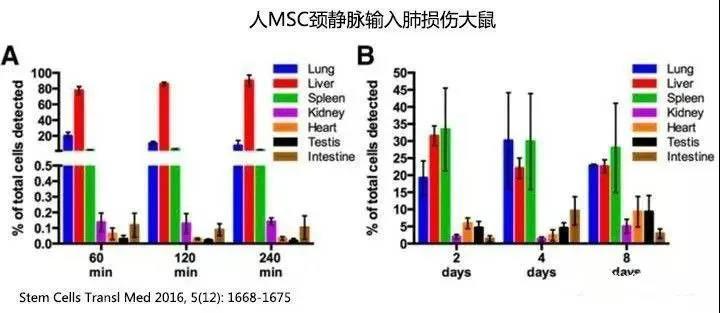

One hour after human MSCs were administered via the rat's jugular vein, the number of detectable human MSCs in the rats’ bodies dropped to approximately 82%, and by day 8, only 0.06% remained detectable. Most of the cells were found in the lungs, liver, and spleen, though a small fraction also appeared in the kidneys, small intestine, and testes. Notably, over time (from 2 to 8 days), the concentration of MSCs in the testes slightly increased—from 4.6% to 9.3% (as indicated by the black bars). (Refer to the figure below; note that the percentages shown represent the proportion of cells still detectable within the body, not the total number of cells initially infused.)

▼Figure - Intravenous Injection of MSCs into Rat Jugular Vein▼

The baboon experiment demonstrated that after peripheral intravenous infusion, there was no significant difference in the distribution of autologous versus allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow within the body. MSCs sourced from umbilical cord blood, however, tended to pass more readily through the lungs compared to bone marrow-derived MSCs. Moreover, the older the donor, the greater the tendency for bone marrow-derived MSCs to accumulate in the lungs. Notably, the number of MSCs retained in the lungs was closely linked to the levels of integrins α4 and α6 expressed on their surface—higher expression of these integrins correlated with reduced lung retention.

After peripheral intravenous infusion of MSCs, most of the cells remain trapped in the lungs before being carried via the bloodstream to the liver, kidneys, and spleen. While MSCs are distributed throughout the entire lung, some studies have shown that the right lung tends to accumulate more MSCs than the left, whereas other research indicates the opposite—more MSCs gather in the left lung compared to the right.

One hour after MSC injection, 50–60% of the MSCs remain trapped in the lungs, a figure that drops to 30% by 3 hours and stays relatively stable up to 96 hours. In cases where pulmonary injury is present, MSC retention in the lungs significantly increases—up to as high as 83%. Although most MSCs administered via peripheral intravenous infusion are initially trapped and cleared in the lungs, these cells can be activated by the local microenvironment within the lung, prompting them to secrete large amounts of the anti-inflammatory factor TSG-6. This process helps reduce inflammation and minimizes the size of the ischemic area following myocardial infarction.

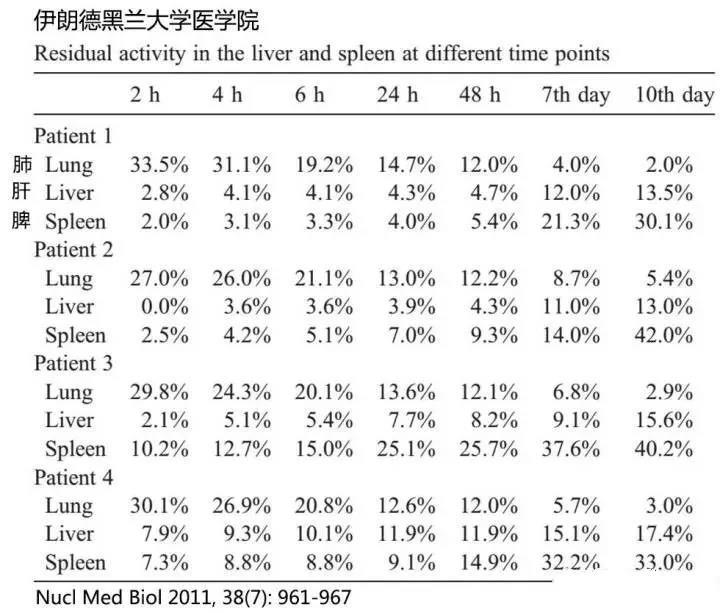

In patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, after ex vivo expansion of autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs, the labeled MSCs—marked with 111In-oxine (a radioactive tracer)—were administered via peripheral intravenous infusion. At various time points, these labeled MSCs were monitored, revealing that, over time, the number of MSCs retained in the lungs gradually decreased, while their accumulation in the liver and spleen steadily increased. Notably, the spleen harbored a greater number of MSCs compared to the liver (see figure below).

▼Figure – Comparison of lung, spleen, and liver cell counts after MSC infusion▼

It has long been demonstrated that peripherally administered MSCs can migrate in small numbers to the bone marrow of the limbs, where they successfully engraft. However, when treated with vasodilators, the number of MSCs migrating to the bone marrow increases by up to 50%. Once inside the bone marrow, these MSCs can persist for an impressive maximum of 76 days. Notably, MSCs cultured in vitro beyond 12 passages—or those derived from older donors—show a significantly reduced ability to migrate effectively into the bone marrow. Interestingly, following irradiation-induced damage to the bone marrow, the number of MSCs migrating to the injured site actually rises. Importantly, intravenously infused MSCs also have the remarkable capacity to migrate into the spinal cord, providing a strong experimental foundation for using peripheral MSC infusion as a therapeutic approach in spinal cord injury treatment.

Comparison of Different Approaches

A pig model of myocardial infarction was established, and bone marrow-derived MSCs were delivered via three different routes—peripheral vein, coronary artery injection, and intramyocardial injection. Fourteen days later, the number of MSCs at the infarcted myocardial site was assessed. The results showed that coronary artery injection yielded the most effective therapeutic outcome, with the highest number of MSCs successfully migrating to the ischemic area. Followed by intramyocardial injection, while no MSCs were detected locally in the ischemic region after peripheral vein delivery. Notably, even when MSCs were injected directly into the heart, approximately 10% still entered the systemic circulation and subsequently migrated to the lungs and liver.

We established mouse models of osteoarthritis and arthritis, administered human adipose-derived MSCs (mesenchymal stem cells) via tail-vein injection, and found that the human MSCs were no longer detectable in the mice after 10 days. However, when human adipose MSCs were locally injected directly into the joint cavity, they remained detectable even after 10 days. These findings suggest that systemic intravenous delivery of MSCs leads to faster clearance from the body compared to localized intra-articular injection.

Ten days after intravenous injection of MSCs into the external carotid artery of rats, MSCs were still detectable in the cerebral cortex. Moreover, MSCs that crossed the blood-brain barrier even migrated to the contralateral brain hemisphere—yet no MSCs from peripheral vein injections could be detected within the brain itself.

Active chemotactic migration

MSC cells exhibit high expression of chemokine receptors, enabling them to sensitively detect and bind to chemokines in the body. They migrate along the concentration gradient of these chemokines, moving from areas of lower to higher concentrations. For instance, substance P released by damaged tissues creates an in vivo concentration gradient, actively attracting MSCs to migrate toward the injury site for repair. Even intravenous injection of substance P can mobilize endogenous MSCs into the bloodstream, guiding them to the injured area and enhancing tissue regeneration. In cases of cardiac myocardial damage, the release of chemokines at the injury site effectively recruits intravenously administered MSCs, allowing them to home in on the damaged heart tissue—where they can persist for up to 7 days.

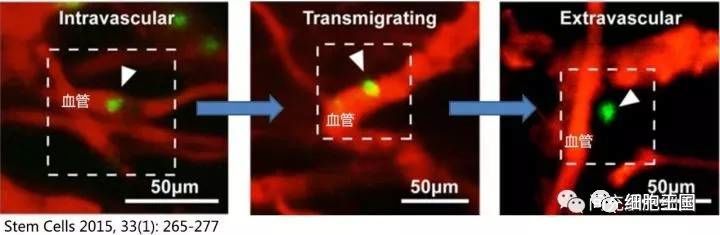

MSC possess a remarkable ability to penetrate blood vessels—a capability that remains unaffected by changes in vascular permeability, as clearly demonstrated in animal studies. For instance, when a mouse model of skin inflammation was established and MSC were administered via intravenous injection, approximately 47.8% of the MSC were observed to cross the vessel walls and migrate into muscle tissue within just 2 hours (illustrated in the schematic diagram of MSC penetrating blood vessels).

Conclusion

Different experiments have shown that the persistence time of MSCs within the body varies significantly. When administered via peripheral vein infusion, MSCs exhibit a relatively consistent distribution throughout the organism—first accumulating in the lungs. A small fraction of these MSCs manages to bypass the lungs and reach highly vascularized organs such as the liver, spleen, kidneys, and pancreas, while an even smaller subset migrates to the bone marrow.

Based on current research findings, whether administered via local or systemic injection, and regardless of whether the MSCs are autologous or allogeneic, the body gradually clears these cells. The rate of clearance depends on multiple factors, including the host’s immune system, the mode of delivery, the tissue source of the cells, the age of the cell donor, and the duration of ex vivo culture. This also suggests that the therapeutic effects of a single MSC infusion may not be long-lasting.

Related News