What lesson does the passing of Yang Junyong, who played Jia Rong in the 1987 version of "Dream of the Red Chamber," remind us of?

2021-11-19

Recently, Yang Junyong, who played Jia Rong in the 1987 TV adaptation of "Dream of the Red Chamber," passed away unexpectedly from a sudden heart attack at the age of 57. His untimely departure has left many feeling deeply saddened—but it also serves as a stark reminder that autumn and winter are peak seasons for cardiovascular diseases, making it especially crucial to remain vigilant against the risk of acute myocardial infarction.

In recent years, with China's rapid economic growth, shifting lifestyles, and the accelerating pace of population aging, the incidence and mortality rates of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have been steadily increasing year by year. As a result, cardiovascular diseases have become the leading cause of death in our country. [1] According to the Markov model prediction, China will see 21 million additional acute coronary events and 7 million cardiovascular-related deaths over the next 20 years. [2] Between 2001 and 2011, the number of Chinese hospital patients admitted for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) quadrupled, rising from 3.50 per 100,000 to 15.40 per 100,000. [3] Moreover, the AMI mortality rate has shown a rapid upward trend: from 2002 to 2015, it rose from 12.00 per 100,000 population in rural areas to 70.09 per 100,000, while in urban areas, it climbed from 16.46 to 56.38 per 100,000. [4] 。

Is a heart attack treatable?

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a major disease that poses a significant threat to human health. In developed countries, it is known as the "number one killer" and remains a leading cause of death worldwide.

When treating patients with myocardial infarction using conventional methods, the primary principle for doctors is to promptly open the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart, restoring myocardial blood flow as quickly as possible. The main approaches include thrombolysis and interventional therapy. Thrombolysis involves administering medications to dissolve blood clots and restore smooth blood circulation; this method achieves a vessel patency rate of 50% to 70%, though it can lead to a range of side effects when high doses of medication are used. Interventional therapy, on the other hand, involves surgically removing clots and implanting stents into blocked vessels to keep them open and ensure unobstructed blood flow. However, this procedure is costly and carries significant risks. In severe cases, heart transplantation may be considered—but it faces challenges such as organ shortages and immune rejection, limiting its widespread adoption.

It is evident that while treatments such as medications, interventions, and heart transplantation can partially alleviate myocardial ischemia, none of them can fundamentally restore infarcted heart muscle.

Inflammation is the main culprit behind adverse outcomes following a heart attack.

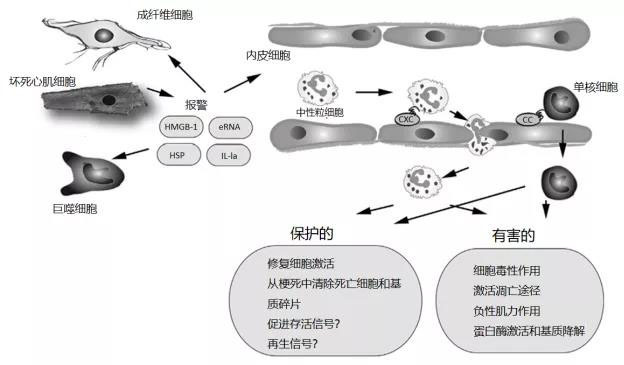

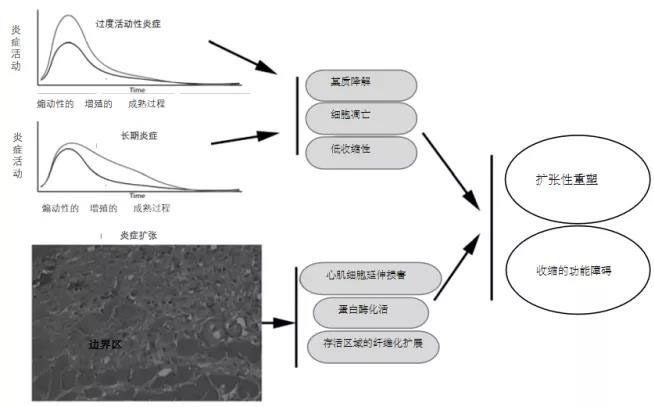

Currently, emergency treatment for myocardial infarction has proven highly effective, yet it still fails to halt the progressive adverse remodeling of the left ventricle. [5] Upon investigation, it was found that the pro-inflammatory immune response triggered after a heart attack acts as a double-edged sword in myocardial healing (as shown in Figure 1): While a moderate inflammatory response helps clear dead cells from the injury site and promotes cardiac repair, excessive activation of the inflammatory cascade can spur a series of cellular reactions (illustrated in Figure 2), potentially prolonging tissue damage and leading to adverse ventricular remodeling. [6-9] Therefore, an excessive immune/inflammatory response may be a key contributor to the progressive myocardial dysfunction observed in these patients.

Figure 1. The inflammatory response following myocardial infarction exerts both protective and detrimental effects on the injured heart. Necrotic cardiomyocytes release danger signals that trigger an innate immune response, leading to the induction of cytokines and chemokines. CXC and CC chemokines bind to glycosaminoglycans on the endothelial surface, facilitating the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the infarcted area. While these infiltrating leukocytes provide both broad protective and harmful effects to the damaged heart, it has been suggested that neutrophils may actually prolong ischemic injury by exerting cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic actions on cardiomyocytes. Additionally, secretory products derived from leukocytes could impair cardiac contractility, while proteases might exacerbate matrix degradation, ultimately contributing to adverse remodeling of the infarcted heart. On the other hand, some subsets of infiltrating leukocytes exhibit protective roles, as they can engulf dead cells and matrix debris, and even promote tissue repair by activating endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Recent studies have also highlighted that specific subsets of myeloid cells may play a beneficial role in cardioprotection by enhancing cell survival and regeneration. eRNA, extracellular RNA; HMGB-1, a highly conserved nuclear DNA-binding protein; HSP, heat shock protein; IL-1α, interleukin-1 alpha.

Figure 2. The consequences of excessive, prolonged, and exaggerated inflammatory responses are adverse cardiac remodeling following infarction. Hyperactive or chronic inflammation can exacerbate matrix degradation by promoting protease activation. Increased cytokine expression may enhance cardiomyocyte apoptosis while simultaneously impairing contractile function. Moreover, impaired spatial suppression of the post-infarct inflammatory response could lead to the expansion of inflammatory damage even in areas of viable myocardium, thereby contributing to widespread fibrosis. Dysregulated negative feedback mechanisms of post-infarct inflammation may further fuel unfavorable dilation remodeling and worsen contractile dysfunction.

This discovery suggests to researchers the need to identify a substance or method capable of modulating the cellular effects and molecular signaling involved in post-infarction inflammation, thereby preventing adverse cardiac remodeling and progressive heart dysfunction.

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy treats cardiac inflammation and improves heart function.

In 2017, Stemedica published a study titled "Systemic Anti-Inflammatory Effects Improve Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischemic Cardiomyopathy" in the internationally renowned academic journal Circulation Research. [10] A study revealed that intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can mitigate the progressive decline in left ventricular function and adverse remodeling in mice with large-area myocardial infarction. In ischemic cardiomyopathy, MSC treatment significantly improves left ventricular performance, partly through their systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

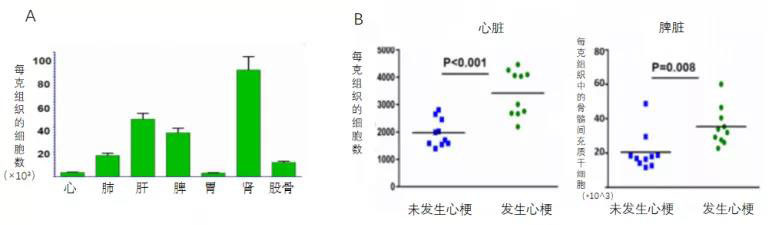

First, it was previously believed that after stem cells were transplanted into damaged heart tissue, their functional repair ultimately relied on the direct replacement of exogenous stem cells and the stimulation of endogenous cardiac cell regeneration. However, in this study, researchers found that 24 hours post-AMI in mice, MSCs labeled with fluorescence and tracked via intravenous injection into the left anterior descending coronary artery showed high concentrations of cells in the liver, spleen, and kidneys—while only a small fraction actually migrated to the heart (Figure 3A). Notably, compared to hearts from animals without myocardial infarction, the spleens of AMI mice exhibited a significant accumulation of MSCs, suggesting that AMI triggers systemic anti-inflammatory signals, thereby promoting the homing and retention of MSCs in the spleen.

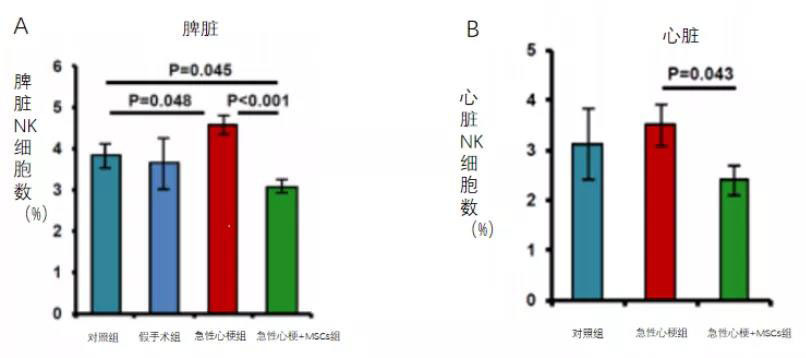

Secondly, researchers found that intravenous injection of human-derived mesenchymal stem cells into rats on day 7 after myocardial infarction significantly increased NK cells in the spleen of mice at 7 days post-AMI, while MSC treatment markedly induced a reduction in NK cells within the spleen (Figure 4A). A similar MSC-induced decrease in NK cells was also observed in the heart (Figure 3B).

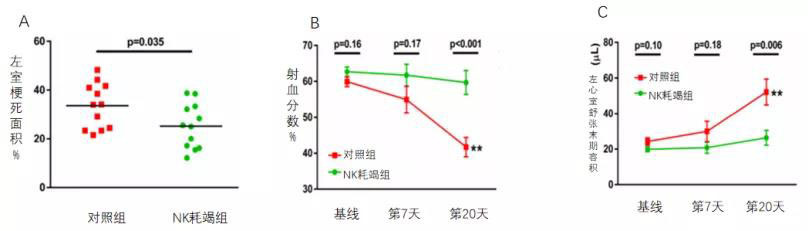

So, does the reduction of NK cells in the myocardium directly contribute to improved cardiac function? In their subsequent experiments, the researchers found that mice treated with an anti-NK1.1 antibody-mediated depletion of NK cells 24 hours before AMI exhibited a significantly smaller infarct area 20 days post-MI (Figure 5A). Moreover, NK cell depletion prior to AMI markedly attenuated the deterioration of cardiac function following the event. Compared to the control group, the NK-depleted group showed a notably reduced infarct size (Figure 5A), a significant increase in ejection fraction (Figure 5B), and a pronounced decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic volume (Figure 5C).

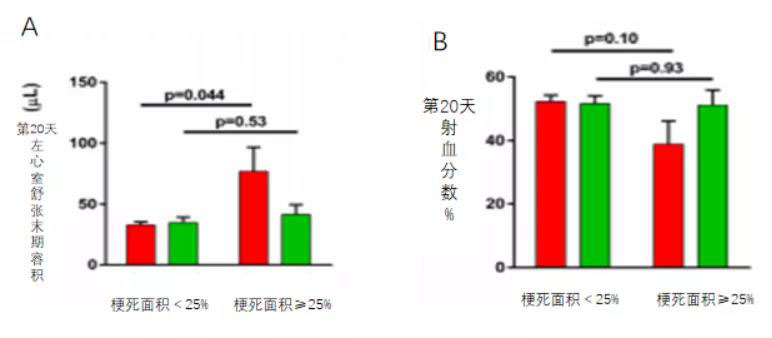

More interestingly, comparing the treatment outcomes in mice with small versus large infarcts revealed that MSC therapy improved adverse left ventricular remodeling—and these benefits were particularly pronounced in mice with MIs accounting for ≥25% of the left ventricle (moderate infarct size of 25%). In this subgroup, MSC treatment prevented the statistically significant increase in end-diastolic volume observed in the control group (Figure 6B), while also showing a trend toward preventing reductions in LVEF (Figure 6A).

Figure 6A shows that, when comparing treatment outcomes in mice with small versus large infarcts, MSC therapy significantly improved adverse left ventricular remodeling—and these benefits were particularly pronounced in mice with MIs ≥ 25% of the LV (moderate infarct size of 25%). Notably, MSC treatment prevented the marked increase in end-diastolic volume observed in the control group.

Figure 6B shows that, when comparing treatment outcomes in mice with small versus large infarcts, MSC therapy significantly improved adverse left ventricular remodeling—and these benefits were particularly pronounced in mice with MIs ≥ 25% of the left ventricle (moderate infarct size of 25%). Notably, MSC treatment effectively halted the trend toward reduced LVEF observed in the control group.

Stemecida's research has provided the medical community with fresh insights into the treatment of myocardial infarction. After intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), these cells naturally home to tissues such as the heart muscle, spleen, and kidneys. By reducing local myocardial inflammation and systemic inflammatory responses, MSCs help improve cardiac function and reverse adverse left ventricular remodeling. Intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells holds promise as a practical, safe, and effective clinical strategy for treating acute myocardial infarction.

References:

[1] Moran A, Gu D, Zhao D. Future cardiovascular disease in China: Markov model and risk factor scenario projections from the Coronary Heart Disease Policy Model China[J]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2010, 3(3):243–252.

[2] Li J, Li X, Wang Q, et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-Retrospective Acute Myocardial Infarction Study): a retrospective analysis of hospital data[J]. The Lancet, 2015, 385(9966):441-51.

[3] Chen Weiwei, Gao Runlin, Liu Lisheng, et al. Summary of the "China Cardiovascular Disease Report 2017" [J]. Chinese Journal of Circulation, 2018, 33(1):1-8.

[4] O′Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines [J]. Circulation, 2013, 127(4):362–425.

[5] Westman PC, Lipinski MJ, Luger D, Waksman R, Bonow RO, Wu E, Epstein SE. Inflammation as a Driver of Adverse Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2050–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.073.

[6] Reinecke H, Minami E, Zhu WZ, Laflamme MA. Cardiogenic differentiation and transdifferentiation of progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2008; 103:1058–1071. [PubMed: 18988903]

[7] Entman ML, Youker K, Shoji T, et al. Neutrophil-induced oxidative injury of cardiac myocytes: a compartmentalized system requiring CD11b/CD18-ICAM-1 adhesion. J Clin Invest. 1992; 90:1335–1345. [PubMed: 1357003]

[8] Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. Targeting inflammatory pathways in myocardial infarction. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013; 43:986–995. [PubMed: 23772948]

[9] Faxon DP, Gibbons RJ, Chronos NA, Gurbel PA, Sheehan F. The effect of CD11/CD18 integrin receptor blockade on infarct size in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with direct angioplasty: results from the HALT-MI study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 40:1199–1204. [PubMed: 12383565]

[10] Systemic Anti-Inflammatory Effects Improve Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

Related News